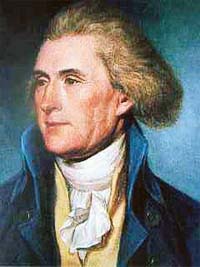

I finally finished reading Joseph Ellis' book subtitled, The Character of Thomas Jefferson, last night. (In addition to being a slow reader, I also read several books at the same time, and I read this book particularly slowly at first.)

I finally finished reading Joseph Ellis' book subtitled, The Character of Thomas Jefferson, last night. (In addition to being a slow reader, I also read several books at the same time, and I read this book particularly slowly at first.)Two points:

(1) I've never been a fan of Thomas Jefferson's. I'm even less so now.

Idealists generally assume that because they are trustworthy and pure, they're incapable of doing or saying anything wrong. But these are the very people capable of doing the most wrong, as well as most rapidly violating their own principles.

Jefferson always exhibited hypocrisy and was so adept at denial, he never knew that he was hypocritical.

Ostensibly an advocate of equality and emancipation, he was a reactionary when it came to any attempts to limit or end slavery.

A believer in limited government, Jefferson nonetheless felt little hesitation about entering a probably unconstitutional usurpation of Congressional power when he bought the Louisiana territory from France.

An alleged believer in civility, he financed the most scurrilous and unconscionable newspaper attacks on George Washington, while sitting in his Cabinet, all the while denying it. (He did the same thing to John Adams when he served as Adams' Vice President.)

Jefferson's most enduring personal trait, one which shone through his public service was running away from conflict. He did this when he was governor of Virginia, secretary of State, and President. He virtually holed himself up in Monticello during his second term as president, particularly frustrating his secretary of State and protege James Madison, when he should have been doing his job.

Unlike most of the other members of the Revolutionary generation, Jefferson thought that the break from England was all about liberty, at the expense of society. Except when he was president, Jefferson believed that the individual reigned supreme. (Of course, that meant only white male individuals to Jefferson.) But the more enlightened Washington, Adams, Hamilton, and even Madison understood that freedom without mutual responsibility and accountability is anarchy. Jefferson had a naive belief in the basic purity of (white) human beings and held that if they were given liberty, they could be counted on to do the right things.

Jefferson also had contempt for the Constitution. Ellis points out that people like Adams, Madison, and Monroe constantly had to correct Jefferson's misunderstandings and misapplications of the Constitution. In France at the time the document was drafted, he always had misgivings about it. Again, except for his presidential tenure--at least the first term, when he displayed little hesitiation about engaging in an almost imperial presidency--Jefferson believed that the House of Representatives should be the preeminent institution of the federal system.

He also believed that if any region of the country should become predominantly urban and dependent on manufacture, the other regions should secede. Such was his regard for the United States of America.

Ellis presents a balanced picture of Jefferson. Those who admire him will like this book as much as I did.

(2) American Sphinx won the National Book Award and it deserved recognition. While it suffers from some of Ellis' tendency to use twenty words when he could use three and a seeming desire to prove how smart he is, it's still a good one, the best one he's written. (By the way, in these two characteristics--the tendency to loquaciousness and the need to show his intelligence--he's not as bad as Edmund Morris.)

I recommend the book.

No comments:

Post a Comment