| You Are Most Like Richard Nixon |

Oh sure, you give people plenty of reasons to call you "Tricky Dick." But you're actually quite diplomatic, even though you secretly hate your enemies. |

A sinner saved by the grace of God given to those with faith in the crucified and risen Jesus Christ. Period.

Saturday, July 08, 2006

I'm Like Richard Nixon?

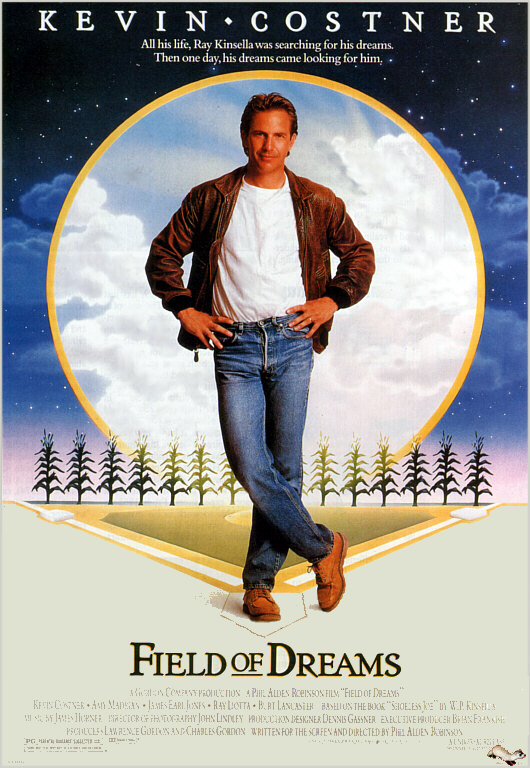

More on 'Field of Dreams'...and the 'Table of Dreams'

Charlie Lehardy, the insightful author of the blog, AnotherThink, and a contributor to the group blog, Think Christian, left a typically insightful comment at this post, where I presented my son Philip's reflections on the movie, Field of Dreams. Charlie wrote:

Charlie Lehardy, the insightful author of the blog, AnotherThink, and a contributor to the group blog, Think Christian, left a typically insightful comment at this post, where I presented my son Philip's reflections on the movie, Field of Dreams. Charlie wrote:Philip has written a great post about a very special movie. I always cry at the end, too, and I've seen it a dozen times. Ray Kinsella serves as a stand in for a great many boys and men who grow up alienated from their fathers in some way, and deeply regretting the void that is there where their father's love should be.I was so taken with Charlie's analysis of the film that I wrote this response:

The dream is about reconciliation and the restoration of the sort of father son relationship every boy wishes he could have, but too few experience. I'll bet there are millions of men who identify with Ray Kinsella and his yearning to have a game of catch with his dad.

Thanks, Philip.

Charlie:

Thanks once again for leaving insightful comments. I think you're right that the real dream of Field of Dreams is one of "reconciliation and...restoration."

Back when this film was first released, I did a Maundy Thursday sermon called, "Our Table of Dreams." It was about Holy Communion.

It was built, first of all, on the fact that when Jesus instituted the Sacrament, He said to "do this in remembrance of me." The word we translate as remembrance is, in the original Greek, a form of the word, anamnesis.

Containing the root of our word for amnesia, anamnesis is nonetheless about much more than doing the opposite of forgetting. In Holy Communion, we do more than have a memory of some dusty, obscure past event. By the power of God's Word and Jesus' promise, we are re-membered with God and with every person, in heaven and on earth, past, present, and future, who has hoped in God and shared this meal.

As on the field of dreams in the movie, eternity invades our time-bound world and we come in actual contact--by hearing God's Word and tasting the bread and the wine--with God and the timelessness of His eternity.

But something else happens to us in Communion that's akin to Ray Kinsella's field, I think. We are reconciled to God, Who forgives our sins through the Sacrament, per Jesus' promise. And, as we join saints above and saints below in humbly being fed by our Lord, we are reconciled to one another. No more airs about self-sufficiency. No more pretense of a righteousness that makes us better than others. We confess our humanity and our sin and our common need to be fed and led by God. In a humble faith that receives God's gifts, we are made one with each other.

Reconciliation and restoration are the things we most crave in life, even when, like Ray Kinsella and his father, we don't know it. We crave reconciliation with each other, to be sure. We crave it most of all, with our heavenly Father. In Christ, that reconciliation happens for all who repent--turn from sin--and receive Christ as God and Savior by faith in Him. Through the Sacrament, the altar becomes our table of dreams and God helps us to be reconciled with Him, remembered to Him, all along the imperfect trail we saved-but-sin-plagued saints follow on our way to eternity.

God bless you, Charlie!

Mark

Do You Know Any Helicopter Parents?

Friday's Cincinnati Enquirer introduced us to the latter-day apron-stringing parents, beginning with the story of one helicopter parent:

There was once a freshman college student who could not find her classroom. So she fired up her cell phone and called her mom. Mom, miles away, called the college, retrieved the necessary information, then rang her daughter. Classroom found, problem solved.How is it that some Baby Boomer parents who defiantly traversed the generation gap to get free of their parents now are reluctant to let their kids grow up? And how is it that their kids don't mind?

James Slager is not making this up.

He's seen a lot of things in his 23 years at Miami University, where he's senior director of student health services, but what he's seen in recent years is an unrivaled closeness, even a dependency, between college students and their parents - a generation of children who are "over-cared for" and parents who are "overly involved," he said.

"Parents think they're doing the right thing," Slager said. Their children, though, "need to learn to grow up."

These parents are referred to - not always kindly - as "helicopter parents" because they, well, hover. At the college level, they demand to see their children's grades and learn when their children visit health services, information that's restricted without student permission. They chew out professors for bad grades and call to wake their kids for class.

They pay the bills, buy the groceries, make the dorm-room beds.

And their children don't mind.

Although our son is temporarily back at home following college graduation and our daughter lives but a few miles from us after her 2005 wedding, neither my wife or I have any desire to micromanage their lives.

In fact, it's a relief not to have to be involved in their decision-making. We love being able to tell them when they ask where such-and-such is, for example, that we don't know and that it's not our job to know!

We'll always be there for our children, of course. But being there for them doesn't mean that we treat them like infants! I've always felt that parents had a few simple tasks:

- To introduce their kids to the God made known in Jesus Christ

- To prepare them for living as adults

It seems to me that Helicopter Parents have somehow fallen measure the worth of their lives on how dependent their kids are on them. But crippling our kids to salve our own egos and desire to be needed isn't parental responsibility. It's the opposite of responsibility!

Phil's "Reflections after watching 'Field of Dreams'"

I couldn't help but reproduce what my son, Philip, wrote about watching Field of Dreams last night. Here it is:

My brother-in-law had turned on ESPN and they were playing Field of Dreams. It was pretty much over after that. You [could] forget about me doing anything else or being anywhere else; I was going to be watching that movie until the very end. My girlfriend at the time came in and asked what we were doing. I said we were watching Field of Dreams.

"Is it a DVD?" she asked.

"No, its on ESPN right now," I replied.

"Well, don't you have it on DVD?"

"Yes."

"Well, why are you watching it on television if you have it on DVD?" she inquired.

My brother-in-law and I just stared at her, and said, almost simultaneously, "Because it's Field of Dreams." We then turned around and continued to watch the rest of the movie, convinced we had just heard the dumbest question in all of human history.

Depending on who you are, one side of this argument will seem insane, while the other point of view is a statement of the most obvious truth. For my ex-girlfriend, there was no reason to watch a movie when one owned [it] and could pop it into the DVD player at one's leisure. On the whole, I would agree with this assessment. There are plenty of shows and movies that I will turn off when company has come over or when I want to be close to a person whom I care about a great deal.

However, for my brother-in-law, my father, myself, and I am willing to bet, most of the male population in America, this particular film is the exception that proves the rule. To ask why I am watching this movie instead of doing something else is just crazy talk, plain and simple. It is my second favorite film of all time and is one of the few films where I am almost guaranteed to cry at the end.

I mention this story because Field of Dreams was on again tonight. I watched it with my dad and sure enough, we both were about to cry when the last scene was being played.

Field of Dreams is the story of Ray Kinsella, played by Kevin Costner. Costner begins the film by narrating Kinsella's early life and the life of his father. (We come to find out later in the film that he rebelled against his dad but loved him. And while Kinsella has lived a good life, he has one great regret about never letting his dad know how much he loved and respected him before his father died.) After this prologue of sorts we are introduced to Ray Kinsella, now a young farmer and family man who hears voices and later sees in a vision that he needs to build a baseball field in the middle of his corn field. After building it, baseball players from the past come to practice at first, and then to actually play. There are other goals that the voice says that Kinsella must [pursue], like finding the world-weary Terrence Mann (played by James Earl Jones) and the crestfallen Dr. Graham (played by the late Burt Lancaster). But at the center of the film is Kinsella's blind obedience to build this baseball diamond and travel up and down the Eastern United States without really asking "what's in it for me". (At least not until the end of the film.)

If the movie sounds far-out, well, it is. But, it's not crazy. It is pure Americana and combines some of the best things in this world: baseball, faith, America, baseball, family, unexpected friendships, happy endings, and of course, baseball. The film critic Roger Ebert said that Field of Dreams "is the kind of movie Frank Capra might have directed, and James Stewart might have starred in -- a movie about dreams."

This might have something to do with why I love this film so much. I will say that in my opinion, one of Frank Capra's films, It's a Wonderful Life, is the greatest film ever made and that Field of Dreams is the second greatest film. I am not alone in my first and second picks. My dad happens to agree with me. In fact, I think I just copied these picks from him.

But then again, one of the great themes of this film is how much sons are like their fathers and how most guys, as much as we hate to admit we love another guy, truly care about our fathers. And, I assume fathers gauge how well they've lived their lives by how well their kids turn out.

So, tonight found my father and [me] sitting down watching a movie we owned, being played on a television network. And during the ending, I thought of my dad, the man I respect more than anyone else in the world, a guy who is not well-known, not good looking, and not that successful, but who thinks that I am the greatest guy in the world. And during the last scene of the film, when Ray Kinsella has made his peace with the great regret of his life, the catharsis overwhelms two grown men and we have to fight back tears. Not because of what we saw on screen so much, but because what we saw on screen is really how we feel towards each other.

I know it's kind of mushy to talk about one's father that way, but I don't want to go through my adult life like the protagonist of Field of Dreams. We only have so much time on earth to let our loved ones know how important they are to us. If there is so much talk about the closeness of family in the world, then it shouldn't be odd for us to express our love and admiration for those people.

You may still say that I am crazy for watching a movie that I already own on DVD, but I have my reasons. And you know what? I think it's good and takes a little guts to do something crazy now and again.

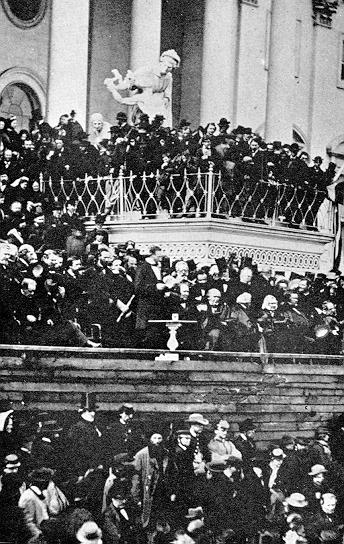

Interpreting Lincoln's Second Inaugural Sermon, Part 4

[We're continuing to analyze Lincoln's second Inaugural Address from a theological perspective. For the complete text of the speech, see here. The text of the address is in bold, followed by my comments.]

Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God's assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men's faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has his own purposes.

1. Here, we come to the nub of things for Lincoln. It's a mystery to him how people who claimed to follow the Prince of Peace, Jesus, the Savior, witnessed to in the Bible, could have fallen into a war. Yet they did.

2. Mysterious to Lincoln, too, is how the South "should dare to ask a just God's assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men's faces." As James Tackach points out, Lincoln's phrasing is rooted in God's words to Adam after he and his wife, Eve, had fallen into sin:

"By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread until you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; you are dust, and to dust you shall return." [Genesis 3:19, New Revised Standard Version]It was never God's plan for human work to be onerous or burdensome. In fact, in work, God invites us to be co-creators with Him, participating in the "Very good!" which He once pronounced over all that He had made. But once sin entered the human picture, work, along with all human activity, was burdened by our alienation from God. What once brought only joy, could now be marred by futility, drudgery, and injustice.

Here, Lincoln seems to be saying, the white slave-owners had arrogated to themselves the God-like right to force other human beings into their service. (Of course, anyone familiar with the God of the Bible knows that He isn't in the practice of forcing anybody to do anything, though He can be fiercely persuasive.) Lincoln seems to be saying that the slave-owners had committed the most basic sin, the one which is present in all our sinning: Pretending, like Adam and Eve had done, to "be like God."

3. Yet, Lincoln immediately takes the sting out of this indictment by quoting Jesus: "but let us judge not that we be not judged." Jesus says words like this in two different places: Matthew 7:1-3 and Luke 6:36-38.

In the Matthew text, we read:

“Do not judge, so that you may not be judged. For with the judgment you make you will be judged, and the measure you give will be the measure you get. Why do you see the speck in your neighbor’s eye, but do not notice the log in your own eye?"It comes as part of that extended time of teaching, the Sermon on the Mount, that begins with the Beatitudes in Matthew, chapter 5. Here, Jesus warns Christians not to be so quick to see the fault in others while simultaneously avoiding acknowledgement of our own sins.

That Lincoln would, at that moment, have chosen to express forbearance and forgiveness toward his Southern enemies is amazing. But it clearly demonstrates that he sees both the North and himself as bearing responsibility for the Civil War. It also bespeaks his desire for national reconciliation.

If Lincoln was citing Jesus' words in the Luke passage, the implications could be slightly different:

"Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful.Here, Jesus' emphasis is on the abundant blessings of God's grace and forgiveness that accrue to those who forego judgment and who embrace mercy.

“Do not judge, and you will not be judged; do not condemn, and you will not be condemned. Forgive, and you will be forgiven; give, and it will be given to you. A good measure, pressed down, shaken together, running over, will be put into your lap; for the measure you give will be the measure you get back.”

In either case, irrespective of nuances, Lincoln's citation of the quote seems to make the same central point: As a repentant sinner guilty of the same sins, Lincoln refused to pass judgment on the sins of the South. Lincoln's humility is extraordinary and stands in marked contrast to that of his successor, Andrew Johnson, who wrecked any chance of having a Reconstruction program along the lines apparently envisioned by Lincoln because of his self-righteousness.

4. Lincoln concludes that the diametrically opposed prayer requests of North and South had not been answered. God, he says, has his own plans.

The most difficult petition of the Lord's Prayer which Jesus taught may be this one: Your will be done. Lincoln's words, "The Almighty has his own purposes" constitute a confession that God is God and that we mortals aren't. They're also a submission to the will of God. He goes on now to strive to understand God's will for the war's continuation.

5. One of the perennial mysteries for persons of faith is why God the Bible reveals to be both loving and all-powerful allows suffering, such as that experienced on a mass scale during the Civil War. Sometimes, the Bible asserts, evil befalls humanity as part of God's plan for us.

The last fourteen chapters of the Old Testament book of Genesis tells the saga of Joseph, the great-grandson of the patriarch Abraham. Sold into slavery by his brothers, Joseph's experiences an extended period of pain and suffering. Yet, after his life had followed plot twists and turns that would make Dickens proud, Joseph ended up functioning as prime minister of Egypt, with the power to get revenge on his brothers. Yet Joseph saw the blessing in the pain. His ascendancy to power enabled him to save the lives of many, including his own family. He was certain that this was what God had wanted to happen and that his agony along the way had been necessary to ensure that outcome. With magnanimity, Joseph tells his brothers, fearful of his vengeance, "Even though you intended to do harm to me, God intended it for good, in order to preserve a numerous people, as he is doing today." (Genesis 50:20)

Sometimes, God allows suffering as a means of chastening us. In Second Corinthians 12, the apostle Paul talks about how God allowed him to suffer from some malady he refers to only as a "thorn in the flesh." God, in fact, had refused Paul's prayer requests for relief or healing three different times. Why? Paul says that it was to keep him from becoming too elated with spiritual ecstasies he'd experienced, to keep him relying not on himself, but on God. "So, I will boast all the more gladly of my weaknesses, so that the power of Christ may dwell in me. Therefore I am content with weaknesses, insults, hardships, persecutions, and calamities for the sake of Christ; for whenever I am weak, then I am strong." (Second Corinthians 12:10)

Of course, both Paul and Joseph were believers who sought to follow God, yet suffered. But what happens when a nation deliberately, unrepentantly sins, as the United States did in preserving and perpetuating slavery? Lincoln concluded that the terrible war that had consumed the United States for the preceding four years was something God had allowed as part of the process of disgorging the evil of slavery from America's national life.

"Woe unto the world because of offences! for it must needs be that offences come; but woe to that man by whom the offence cometh!"

1. Here, Lincoln quotes Jesus directly. The words come from an incident recounted in Matthew 18:1-5 in which Jesus upbraids His disciples for trying to send little children away from Him. Jesus goes on to warn His disciples aginst being the agents by which others fall into sin.

Here, I think Tackach wildly misunderstands Lincoln. He writes:

Lincoln, patronizingly, had viewed the slaves as a meek, almost childlike people; to the slaves, Lincoln was Father Abraham. By offending enslaved people, the nation had failed to heed Christ's warning about offending "these little ones," and now the nation must pay for that offense.But Lincoln makes no mention of "little ones." For Tackach's argument to make sense, the white population of the United States would have to be accused by Lincoln of causing the slaves to sin. He doesn't even imply this. Lincoln's interest in the passage is solely based on the culpability of those who sin, as he indicts the North, the South, and him for doing by maintaining or being complicit with slavery.

If we shall suppose that American Slavery is one of those offences which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offence came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a Living God always ascribe to Him?

1. In his maturity, the thing that once chased Lincoln away from faith in a personal, loving God is now the thing he accepts, intellectual difficulties nothwithstanding. As a younger man, the tragedy of his life caused him to doubt or disbelieve in the immanence of God, that is, the presence of God even in the midst of tragedy and the ambiguities of a sin-drenched world.

Lincoln could now contemplate the possibility that a God of love might countenance and even direct the coming of a great evil like the Civil War as the appropriate and cleansing outcome of a nation's sin. Lincoln might have pointed to the words of the prophet Daniel to buttress his view:

"Praise be to the name of God for ever and ever;God, in this view, is involved in human history and while He allows human beings to make evil choices, He will not allow evil to go on unchallenged. The problem, according to the Biblical view, is that we human beings confuse God's patience when we perpetrate evil as permission or license or as evidence of God's absence. In fact, God's patience is our opportunity for repentance. It was an opportunity repeatedly ignored in the past. Now, Lincoln concluded, the US was experiencing the terrible reckoning.

wisdom and power are his.

He changes times and seasons;

he sets up kings and deposes them.

He gives wisdom to the wise

and knowledge to the discerning.

He reveals deep and hidden things;

he knows what lies in darkness,

and light dwells with him. (Daniel 2:20-22, The New International Version)

2. What are the attributes of God? As one of my seminary professors, Ron Hals, points out in his fabulous little book, Grace and Faith in the Old Testament, the primary attribute of God, according to both the Old and New Testaments, is God's grace. Grace describes God's acceptance of the repentant in spite of their sins or lack of merit. It was grace that caused God to make the doubting, powerless Hebrews His own chosen people and it was grace that caused God the Son, Jesus Christ, to come into our world offering new life to human beings who, because of their common condition of sin, were alienated from God.

But grace can be misunderstood. More on that in a later installment.

Interpreting Lincoln's Second Inaugural Sermon, Part 3

In the first installment of this series, we established that Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address is so clearly built on at least four Biblical texts--and, as we shall see, on Christian notions of repentance and renewal--that it is more sermon than policy statement.

In the second, we traced the evolution of Lincoln's religious beliefs through 1865.

Now, to the text and an analysis of it. This, I think, will yield some clues as to what Lincoln may have meant in referring to "those divine attributes which the believers in a Living God always ascribe to Him."

Here's the full text of the speech (I've numbered the paragraphs for easy reference):

1. At this second appearing to take the oath of the presidential office, there is less occasion for an extended address than there was at the first. Then a statement, somewhat in detail, of a course to be pursued, seemed fitting and proper. Now, at the expiration of four years, during which public declarations have been constantly called forth on every point and phase of the great contest which still absorbs the attention, and engrosses the energies of the nation, little that is new could be presented. The progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends, is as well known to the public as to myself; and it is, I trust, reasonably satisfactory and encouraging to all. With high hope for the future, no prediction in regard to it is ventured.We can, for now, dispense with discussion of paragraphs 1 and 2, which really serve to set the contextual stage for the main points Lincoln wants to make in the latter two paragraphs. But, in the last installment of the series, we'll come back to them, as an exploration of paragraphs 3 and 4 will help us to better understand what Lincoln says in the foresection of the speech.

2. On the occasion corresponding to this four years ago, all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil war. All dreaded it--all sought to avert it. While the inaugeral [sic] address was being delivered from this place, devoted altogether to saving the Union without war, insurgent agents were in the city seeking to destroy it without war--seeking to dissole [sic] the Union, and divide effects, by negotiation. Both parties deprecated war; but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let it perish. And the war came.

3. One eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the Southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union, even by war; while the government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it. Neither party expected for the war, the magnitude, or the duration, which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God's assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men's faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has his own purposes. "Woe unto the world because of offences! for it must needs be that offences come; but woe to that man by whom the offence cometh!" If we shall suppose that American Slavery is one of those offences which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offence came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a Living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope--fervently do we pray--that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said "the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether"

4. With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan--to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

Paragraph 3:

One eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the Southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war.

1. In saying that the "colored slaves" comprise one-eighth of the US population, Lincoln is tacitly recognizing what many of his time would have been horrified to admit: that those African-Americans who made up the slave population were on an equal footing with whites. The Constitution, of course, hadn't recognized this fact, having ascribed to blacks and Indians the value of three-fifths of a person.

As anyone who has read the transcripts of the Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858 can attest, Lincoln's racial views weren't appreciably more enlightened than those of the Founders. In the early years of his presidency, he still tried to find a means by which African-Americans who had lived in this country for centuries could be sent "back to Africa" or perhaps, to South America.

But Lincoln underwent a conversion experience during his presidency. He came to view African-Americans as the equals of whites. Frederick Douglass said that no white man ever accorded him the sort of unself-conscious and easy-going magnanimity that Lincoln displayed whenever they conversed.

2. Lincoln's statement that slavery "somehow" was "the cause of the war" is remarkable. It's a strong intimation of what will follow. Lincoln will avoid ascribing blame for the Civil War to the South alone. The institution of slavery was a great evil "localized" in the South, of course. But from the beginning, the South practiced slavery and for the sake of unity, the North had countenanced it. Both were to blame for the evil institution and for the evil of the war which it "somehow" caused.

Implicit in Lincoln's recognition of Northern complicity with slavery, is a confession of his own personal complicity with it. Lincoln had never been among the Republican "radicals" or abolitionists. He had been willing to accept the continued existence of slavery in those states where it had existed already, even after the Civil War had begun.

Early in the conflict, he insisted that it was not about slavery, a political construction designed to maintain the loyalty of the border states, which had slavery but remained in the Union. (Nonetheless, Lincoln, with his rational bent of mind, no doubt believed that preserving the Union was a higher value than the disposition of slavery or the slaves.) But his "preserve the Union" stance proved less than inspiring to the North and, Lincoln seems to have ultimately concluded, not accurate. Slavery was the actual cause of the war, the whole nation and its president bore culpability for slavery lasting so long, and now, Lincoln concluded, God had decided that slavery must be ended.

3. Presidents don't generally like to indict their countries or themselves for mistakes or moral blindnesses. Yet these were extraordinary times and Lincoln was an extraordinary man. Lincoln seemed to understand that the post-Civil War era would present his generation with an opportunity analogous to that given the Revolutionary War-generation after their great war had ended: To consciously fashion the identity and organizing principles of a renewed America.

Consonant with the Biblical perspective though, Lincoln realized that new starts cannot be made without first dealing with the sins of the past. Confession is the road to healing. A psalm ascribed to the Old Testament King David says:

Blessed is heTo strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union, even by war; while the government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it.

whose transgressions are forgiven,

whose sins are covered.

Blessed is the man

whose sin the LORD does not count against him

and in whose spirit is no deceit.

When I kept silent,

my bones wasted away

through my groaning all day long.

For day and night

your hand was heavy upon me;

my strength was sapped

as in the heat of summer...

Then I acknowledged my sin to you

and did not cover up my iniquity.

I said, "I will confess

my transgressions to the LORD "—

and you forgave

the guilt of my sin. [Psalm 32:1-5, The New International Version]

1. This is the closest that Lincoln comes to ascribing more blame on the South than the North. Yet, from the rest of the speech, we see that implicit in the clause that says "while the government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it," was a self-indictment and one of the North. They had been guilty of moral laxness in failing to address the issue of slavery. They had been willing to allow the continued trafficking in human beings, if only the unity of the nation could be maintained.

Many in the North had been willing to accept the slave commerce. For example, textile factory owners and workers in New England suppressed any concerns they might have had about slavery because they needed the cotton the slaves cared for and picked.

It wasn't enough to restrict the spread of slavery, Lincoln was saying. The soul of the nation depended on the total abolition of slavery and the exorcism of all the putrid arguments that had been made to justify it, in both the North and the South. It was not possible to compromise with slavery if America was to become the America of its July 4 promise.

For a man like Lincoln, an exponent of American exceptionalism, America nationhood involved more than territorial sovereignty, economic well-being, or military might. In the Gettysburg Address, he had described the conscious beginning of America with those famous words, "Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal."

The United States had not evolved by virtue of language and culture or by the conquests of competing powers. The Founders had decided to birth the United States of America. They had covenanted with each other in the way a man and a woman covenant in marriage and from their union, a new nation was born. That nation had a mission, Lincoln had said: the fostering of freedom for all its citizens in a national community in which all citizens had equal standing.

In the New Testament book of Galatians, the apostle Paul writes that within the Christian community, "There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus." (Galatians 3:28) As a voracious reader of Scripture, Lincoln was no doubt influenced by such constructions. What he understood is that in the eyes of the Creator acknowledged by the Declaration of Independence, all were equal.

The end of slavery was, for Lincoln by the occasion of his second Inaugural, a necessity if America were to maintain its unique status among the family of nations, if it were to fulfill the promise made at its birth, and if it were to save its national soul.

Neither party expected for the war, the magnitude, or the duration, which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding.

1. Here, Lincoln again does something else we seldom see in political leaders. He admits that he and the rest of the country, in both regions, had had no idea how protracted the Civil War would be.

He also admits that he, in 1861, had not anticipated that before the conflict ended, he would sign the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing slaves in the conquered southern states and clearing the way for the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, banning slavery, before the end of 1865, nine months after the Inauguration, eight after Lincoln was cut down.

One element of confession featured prominently in the Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous and taken from the Bible, is the idea that some evil has overtaken the confessor and is so large he or she cannot handle it by themselves. The first step in confession is the honest admission of our helplessness before an evil that has leeched onto and taken control of our lives. Lincoln effectively makes such a confession about slavery in this speech.

It's commonplace to say that in this speech, Lincoln plays the role of an Old Testament prophet, calling the nation to repentance. There's truth to that. But he is just as much playing the role of priest, a function which the New Testament insists, every believer in Christ plays. A priest, according to the Bible, is one who represents the people before God and God before the people. Lincoln courageously plays that dangerous role here.

Gandhi once said, "They say I am a saint trying to be a politician, but I am only a politician trying to be a saint."Perhaps Lincoln, who had always resisted surrender to the God attested to in the Bible, might have said the same thing, considering that the Biblical understanding of a saint is simply one who believes in the God revealed in Jesus Christ.

2. The war had turned out to be "fundamental" and "astounding." From the death and destruction of the Civil War, Lincoln and the nation had learned that we're not always as clever or competent as we think. For a self-made man like Lincoln who believed in rationality, the war was a stunning lesson in the limits of human ingenuity.

Once the war began, he was certain that it must be executed until victory was achieved. But, for a man of Lincoln's sensibilities and sensitivity, every wounded or dead soldier, every widow or orphan resulting from the war, was a repudiation of human hubris and of all human pretense of being in ultimate control.

[More analysis in the next installment of this series.]

Interpreting Lincoln's Second Inaugural Sermon, Part 2

In the first installment of this brief series, I said that Abraham Lincoln's second Inaugural Address, delivered on March 4, 1865, could more readily be referred to as a sermon. In it, the sixteenth president grapples with the meaning of the Civil War which, even then, with Union victories piling up and the Confederacy in its death throes, he was afraid to predict would soon end.

The address is written from a thoroughly theistic perspective. This is amazing when one considers Lincoln's stance toward God and religion through much of his life. He had always been a brooder. Nothing caused him to brood more over the course of his lifetime than the questions of a good God's existence and presence against the backdrop of human tragedy, of which Lincoln experienced more than his share.

As a boy and a young man, Lincoln, a talented mimic, regaled his friends with deadly and disdainful impressions of the backwoods preachers they'd all heard. When his father, Thomas, from whom Lincoln was always distant, embraced an active role in a church in Indiana, the son didn't follow suit and appears to have taken a dim view of all things religious. Lincoln never joined a church, a fact that caused him some difficulty in the 1860 election campaign.

Four great tragedies in the young Lincoln's life seem to have steered him away from anything like a Christian belief in God: the deaths of his mother, his sister, and his sweetheart and the breaking of his engagement to Mary Todd, with whom he would later be reconciled and who he would ultimately marry. When Ann Rutledge, the sweetheart, died, Lincoln found no solace in the Bible. Instead, the rationalist, he dug deeply into Euclidean Mathematics, with its inviolable and consoling certainties. After deciding to break off his engagement to Mary, Lincoln entered a depression so deep that years later, some of his friends reported having feared that he would commit suicide.

Most of his life, Lincoln seemed to fear nothing so much as not being in control. This is a common feature of the self-made man or woman and an impediment to the sort of faith to which Jesus Christ calls people, a faith that trustingly surrenders to the will of God.

Yet, Lincoln always read the Bible and was no casual student. Biblical imagery can be found in many of his best speeches. The address that propelled him toward serious consideration for the Republican presidential nomination in 1860, the Cooper Union speech, was built around the central image of a "house divided" being unable to stand. That image came straight from Jesus, although used by Him in a markedly different way.

Throughout much of his career, Lincoln's use of Biblical allusions and references to God appear to have been motivated not by any deep religious faith, but by a desire to tap into the common culture of a nation in which every literate person was deeply conversant with the Bible. When asked to describe his own religious beliefs, Lincoln had said, "When I do good, I feel good; when I do bad, I feel bad. And that is my religion." Although that might suffice as the statement of a self-directed person of success, it's a long distance from the Christian belief that it's only those who renounce their pretenses of personal sovereignty--who admit their weaknesses--who experience the power of God in their lives.

But just as the tragedies of his early life seem to have driven the young Lincoln away from God toward the apparent certainties of self-reliance, his experiences as President taught him a very different lesson. "I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me," Lincoln wrote in a letter, composed less than one year before he delivered the Second Inaugural Address.

In 1861, Lincoln may have felt that he could handle the crisis of secession with ingenuity, courage, moral suasion, and above all, irrefutable logic, the idol that always vied for his ultimate allegiance. Incoming presidents often enter office bubbling with confidence in their skills and those of their teams. But nothing Lincoln did could stop the coming of the terrible war, a burden that weighed on him so heavily that you see him age through each succeeding year in photos taken of him during his presidency. In addition, a beloved son died and he watched his wife become largely immobilized by her grief. A war that many thought the North could easily end had dragged on for more than four years, leading Lincoln to spend agonizing hours at the War Department telegraph office awaiting news of battles in places like Gettysburg, Antietam, and elsewhere.

Tragedies and the limits of human effort now sent Lincoln into the Bible to look for some explanation. The result was the most unique of all presidential addresses. We'll delve into the details of the Second Inaugural Address as a sermon tomorrow.

[The first installment in this series can be found here.]

Interpreting Lincoln's Second Inaugural Sermon, Part 1

On his radio show earlier this evening, Hugh Hewitt read Abraham Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address, which Lincoln delivered on March 4, 1865. It was given just weeks before the sixteenth president became, in effect, the last fatality of the Civil War, the conflict which was the central subject of the speech.

I was glad to hear Hugh read it. Although often overshadowed by the Gettysburg Address, the Second Inaugural speech deserves at least as much attention because of its wisdom, insight, and unadorned eloquence.

I called to applaud Hugh for reading the address and to share my belief that if Lincoln had exegeted the United States in the Gettysburg Address, he had exegeted the war in the later statement.

In fact, I believe that exegete is precisely the appropriate verb to describe what Lincoln does in both speeches, especially the Second Inaugural Address. Exegesis is the primary discipline of a Christian preacher. It's the critical study and interpretation of a text, usually of a Biblical text. But a preacher must study and interpret more than just a passage of Scripture to communicate truth. A good preacher, my mentor Bruce Schein used to remind us, not only exegetes the text, but also exegetes her or his time.

Twentieth-century theologian Karl Barth put it in another way when he said that the preacher needs to enter the pulpit with a Bible in one hand and a newspaper in the other. By this, he didn't mean that the contents of the newspaper--the things going on in the world--were as important as what's in the Bible. Christians believe that the Bible is God's revealed Word for the human race. But the effective preacher must discern what is happening in the world and apply that Word aptly.

That's exactly what Lincoln did in the Second Inaugural Address. It is much less a political or policy document--in fact, he uses the opening sentences of it to dispense with any discussion of politics or policy--as it is a theological statement. It's a sermon built on no fewer than four Biblical texts. (Matthew 7:1-3; Luke 6:36-38; Psalm 19:7-9; First Peter 4:8) (The discerning will see that I've cited five texts here. But those from Matthew and Luke are roughly parallel in what they quote Jesus as saying, although set in different contexts.)

According to James Takach, the Address was recognized as a sermon by some almost from the beginning:

Congressman Isaac N. Arnold...called [the Address] his [Lincoln's] sermon on the mount...Lincoln's exegetical intepretation of the Civil War is that both North and South bore responsibility for the arrival of the conflict. Although Lincoln initially said that the war was about nothing more than preserving the Union, by 1862, in private conversations and correspondence, he acknowledged, as he did in the Second Inaugural Address, that "somehow," slavery was the root issue of the war.

African Americans who heard the address understood perfectly what Lincoln was saying, and they sensed that the speech had a speical meaning for them. The New York Herald reported that the "Negroes ejaculated, 'bress de Lord' in a low murmur at the end of almost every sentence." They realized that they were hearing a solemn and profound sermon, similar to the ones that they heard so often in their Baptist churches. When Frederick Douglass met Lincoln at an Inauguration Day reception at the White House, Douglass told the president that his address was "a sacred effort."...

Slavery, Lincoln asserted in the Second Inaugural Address, violated God's will. The South was guilty of practicing it. The North was guilty of complicity with it. There had to be a reckoning for slavery and the long and bloody Civil War was that reckoning. How much longer it would last, Lincoln said, was totally up to the God Whose justice was playing out in this long national ordeal.

Toward the end of our brief conversation tonight, Hugh said that he hoped that I, and any other theological types who might be so inclined, would try our hands at exegeting one passage from Lincoln's address:

If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him?What, Hugh wondered, might Lincoln have meant when he spoke of "those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him"?

I will tackle that question. But, before getting there, we will have to trace Lincoln's argument and his allusions, both Biblical and historical. Only then will his reference to commonly-ascribed divine attributes begin to make some kind of sense. I can't claim to know the mind of Lincoln. But by tracing his Biblical and theological footsteps, I think we can reach a plausible conclusion about what he was saying in this extraordinary message. More, hopefully, tomorrow.

[Thanks to Hugh Hewitt for linking to this piece. Okay, so he called me Mark Luther. He tagged me with the wrong name, but the right denomination.]

Thursday, July 06, 2006

Second Pass at This Weekend's Bible Lesson: Second Corinthians 12:2-10

Context:

1. Our lesson comes from a section of Second Corinthians in which Paul derides the foolishness of human beings engaging in spiritual bragging. This is rooted in Paul's oft-repeated belief that holiness and acceptability to God aren't the products of moral or religious superiority. These things are gifts God grants to those willing to admit their need of God's forgiveness and God's power to live, granted to those with faith in Jesus Christ. Martin Luther put it well when he said, "We are all beggars."

2. Specifically, of course, Paul condemns the preachers of spiritual pride we've mentioned more than once as we've been focusing on Second Corinthians during our weekend worship celebrations recently.

3. To get a clear fix on what Paul says in this weekend's lesson, we'll begin our verse-by-verse analysis of what he says with verse 1.

Verse-by-Verse Comments:

1It is necessary to boast; nothing is to be gained by it, but I will go on to visions and revelations of the Lord.

(a) Bragging super-apostles had dazzled the Corinthian Christians with tales of their visions and revelations, mocking Paul for apparently not having such experiences. Paul decided that to refute them, he needed to recount a vision he'd had fourteen years earlier. It's a foolish game, he says, this spiritual bragging. But, in response to what these false preachers are saying about adversity or pain being punishments from God, he would respond.

As the passage unfolds, we'll see that Paul attaches little public value to visions. Visons, like the gift of tongues he addresses in First Corinthians, are primarily about bringing private consolation to individual Christians. Implicit in Paul's telling about his vision here--and, as we will see, in the way he tells it--is his belief that having visions doesn't necessarily prove one's faith or faithfulness. They don't confer bragging rights on the recipient.

(b) Dan Lewis notes the presence in this lesson of an important motif in Paul's two New Testament letters to the spiritually proud and materially wealthy church at Corinth:

The meaning of virtue was one of the prominent ethical discussions in the writings of ancient intellectuals. So-called "virtue lists" abound in classical literature; they typically commend such traits as piety, reverence, excellence, practical knowledge and patience. One quality of character, however, that one never finds in the Greco-Roman "virtue lists" is the trait of weakness.You probably have noticed how often this quality was mentioned by Paul in his Corinthian letters. We are weak... Who is weak and I do not feel weak? If I boast, I will boast about the things that show my weakness. Therefore, I will boast all the more gladly about my weaknesses, so that Christ’s power may rest upon me. Not only does Paul champion weakness in himself, he extols the weakness of Christ. For to be sure, he was crucified in weakness... And then he says about us all, Likewise, we are weak in him... The point is this: true holiness is not a matter of personal power—it is a matter of God’s power in the midst of personal weakness.

The city of Corinth, like many ancient cities, was inundated with the images of power. The impressive temple of Apollo under the brow of the acropolis greeted all visitors to the city. The biennial Isthmian Games featured contests of athleticism and feats of power. Corinth, the “master” of two harbors, was an economic trade center and power-broker for much of the Mediterranean world. Hence, it is not surprising that the cult of power was alive and well among Corinth’s citizenry and even among the Christians who responded to Paul’s preaching. Sometimes the exaltation of power infiltrated even their understanding of the graces and gifts of the Holy Spirit.

2I know a person in Christ who fourteen years ago was caught up to the third heaven—whether in the body or out of the body I do not know; God knows. 3And I know that such a person—whether in the body or out of the body I do not know; God knows— 4was caught up into Paradise and heard things that are not to be told, that no mortal is permitted to repeat.

Paul feels he has little choice but to tell his story, though. He wants to show that God reveals himself and works in the life and graces weak people, at least as much as in those who are strong by the world's standards.

(b) In this section, Paul is going to underscore the themes of God's strength and his own weakness by repeatedly referring to what God knows and what he doesn't know.

(c) Scholars are unable to reconstruct the exact circumstances in which Paul received this vision. Assuming that the letter was written between 54 and 56AD, the incident would have happened about 40-42AD, approximately seven years after Paul's Damascus Road experience, when the one-time enemy of Christianity encountered the risen and ascended Jesus Christ and himself becomes a Jesus-Follower. (Galatians 1:13-17; Acts 9:1-19 [Note on the Acts passage: Paul's original name was Saul.])

(d) "third heaven": The idea of a layered heaven is found in several places in the New Testament.

(e) "Paradise" was a word that originated in the Persian language. It meant garden, referring to something like the formal gardens one might see in England today. The New Interpreter's Bible points out that Jewish literature uses the term for Eden and more generally of a peaceful place that set above the earth. It was also used of the place where God reigns and takes care of His people. This latter use can be found most notably in Jesus' words to the thief on the cross, Luke 23:43.

(f) One interesting construction of this passage is offered by The New Interpeter's Bible, which says that in it, Paul tells two stories, both about himself.

- One is the story of the man close to God, who received an extraordinary vision, revealing things to him of which no mortal may speak.

- The other is of the same man receiving adversity from Satan, but which God allowed to continue in order to keep him from becoming too elated or too proud.

5On behalf of such a one I will boast, but on my own behalf I will not boast, except of my weaknesses. 6But if I wish to boast, I will not be a fool, for I will be speaking the truth. But I refrain from it, so that no one may think better of me than what is seen in me or heard from me, 7(a) even considering the exceptional character of the revelations.

(a) Look, Paul says, the only reason I'm going to boast is to showcase my weaknesses. Whatever good I've done, he says, has come from God. I'll boast in my weaknesses because in them, through the prism of my finitude, you can see God's powerful love.

(b) Paul hopes that the Corinthians will remember him, not for spectacular spiritual events, but for his everyday faithfulness, his daily love for God and neighbor, his pointing to Christ rather than to himself. As the New Interpreter's Bible puts it:

Paul will not use any vision or revelation, no matter how grand, to trump his own day-to-day performance.What's important is the power of God, not the puny pseudo-power of Paul!

7(b)Therefore, to keep me from being too elated, a thorn was given me in the flesh, a messenger of Satan to torment me, to keep me from being too elated. 8Three times I appealed to the Lord about this, that it would leave me, 9but he said to me, “My grace is sufficient for you, for power is made perfect in weakness.” So, I will boast all the more gladly of my weaknesses, so that the power of Christ may dwell in me. 10Therefore I am content with weaknesses, insults, hardships, persecutions, and calamities for the sake of Christ; for whenever I am weak, then I am strong.

(a) The word translated as "thorn" in our Bibles could as easily be called a spike or a stake. In fact, according to several sources, a skolops usually referred to one three different things, each far more dangerous than a thorn:

1. It could be part of a palisade erected for defensive purposes. A palisade was a fence put on the perimeter of a fort or of something else that needed protecting. The palisade was composed of "pales," stakes on which enemies might impale themselves.(b) Paul's skolops is ill-defined. It may be a physical ailment or something else. There are lots of theories and nothing definitively proven. But it is probable that the church at Corinth was aware of this "weakness" in Paul.

2. A skolops, similarly, might be placed, pointed tips up, in the bottoms of pits dug into the ground. When set like this, they were designed to gore opposing soldiers who might happen to fall into the pits.

3. A skolops might also refer to a device used to impale enemies in torture.

(c) Paul says that the skolops in his flesh was sent by Satan, probably as a way of thwarting him in his faithfulness to Christ. But, Paul says, that in sending this affliction to him, Satan had actually played into God's hand.

This line of thinking readily harks back to two key Old Testament figures. In Genesis, Joseph underwent horrible afflictions because of the jealousy of his brothers. But when he had the opportunity to get revenge, Joseph didn't do it, explaining that while his brothers had meant it for ill, God had good purposes to which he put it all.

A more direct analogy is with Job. In Job's case, Satan was the direct cause of all of Job's afflictions. And God allowed them to come to him.

God doesn't will awful things to happen to us, Job and Paul would both say. But, if, in our weakness, we keep following the God we meet in Jesus Christ, His greatness and power will be experienced by us and seen in us by others.

(d) In spite of Paul asking God three times to remove the skolops from his flesh, God refuses, seeming to tell Paul that His gracious acceptance of Paul was enough. The power of God is difficult to see in people like Paul's super-apostle accusers. Were the things they did rooted in God or in their own power, persuasiveness, wealth, and ingenuity? It was hard to know.

Not so in the diminutive, balding, sometimes boring, and often-suffering Paul. He was too weak to accomplish anything that mattered on his own. He didn't look like the evangelist sent by Central Casting. God shone through powerfully in his weakness.

As I mentioned in my first pass at this lesson, a good Old Testament figure to consider in order to understand Paul's argument here is Gideon. The people of Israel were facing a great battle. But God wouldn't allow them to go into it with a large force. He told Gideon to reduce its size dramatically. Doing so was militarily insane. There was no way his force could defeat the one amassed against them. But God said that he had to lead a tiny army. Only then, once victory had come to them, would they and the whole land of Israel know that it was God Who had fought for them.

(e) It was to demonstrate His power that God refused to take away Paul's skolops. This refusal is analogous to the Father's refusal of Jesus' request that the cup of His death on the cross might pass. The crucifixion was part of the Father's plan, one to which Jesus was submissive in spite of His understandable fears. (Mark 14:36)

(f) The God we know in Jesus Christ still only works in the lives of those who accept their own weakness and His power. God can work in any and all circumstances for our eternal good. (Romans 8:28)

Tuesday, July 04, 2006

First Pass at This Weekend's Bible Lesson: Second Corinthians 12:2-10

Bible Lesson: Second Corinthians 12:2-10:

2I know a person in Christ who fourteen years ago was caught up to the third heaven—whether in the body or out of the body I do not know; God knows. 3And I know that such a person—whether in the body or out of the body I do not know; God knows— 4was caught up into Paradise and heard things that are not to be told, that no mortal is permitted to repeat. 5On behalf of such a one I will boast, but on my own behalf I will not boast, except of my weaknesses. 6But if I wish to boast, I will not be a fool, for I will be speaking the truth. But I refrain from it, so that no one may think better of me than what is seen in me or heard from me, 7even considering the exceptional character of the revelations. Therefore, to keep me from being too elated, a thorn was given me in the flesh, a messenger of Satan to torment me, to keep me from being too elated. 8Three times I appealed to the Lord about this, that it would leave me, 9but he said to me, “My grace is sufficient for you, for power is made perfect in weakness.” So, I will boast all the more gladly of my weaknesses, so that the power of Christ may dwell in me. 10Therefore I am content with weaknesses, insults, hardships, persecutions, and calamities for the sake of Christ; for whenever I am weak, then I am strong.

General Comments:

1. For some sense of what this letter from the apostle Paul to the church in the Greek city of Corinth is all about, see here (look at "General Notes") and here.

2. But a caveat is appropriate here. Some scholars believe that chapters 11 to 13 of our present Biblical book may, in fact, be from an altogether different letter from Paul to the church at Corinth.

There are several reasons for suggesting that this may be so. The most important one is its difference in tone. For example, in Second Corinthians 8:7-15, the passage at which we looked last week, Paul has unpleasant and maybe, unpalatable, things to say to the Corinthian Christians. But he precedes those unpleasant words by extolling the members of the church at Corinth for excelling in many ways, including his love for them. There may be some sarcasm in the words that open that text. Nonetheless, Paul is peaceful and complimentary in his approach to the topic he wants to address with the Corinthians.

Here, though, Paul is directly confrontational, almost combative. At the very least, these chapters represent a decidedly separate portion of the letter. Yet, for all the anger that animates Paul's words here, he remains thoroughly in control, always building on the bedrock of faith in a God Who acts decisively for the human race through Jesus Christ, offering new and everlasting life to all who turn from sin and entrust themselves to Christ.

This feat is all the more amazing when one considers that Paul composed this letter not while sitting at a desk, pen in hand or computer before him. Pen or computer would have allowed him the luxury of crossing things out, editing, and re-drafting certain portions of his writings. Instead, everything was dictated to a secretary, known as an amanuensis. I can't even write, edit, and re-edit simple paragraphs I compose without subsequently finding tons of mistakes. I can't imagine dictating letters that nearly always flow, are thematically consistent, and have clarity! That Paul wrote letters of such quality in this way is a tribute, first, to the Holy Spirit Who inspired him and second, to the clarity of a mind focused on God.

3. The core issue of Second Corinthians, chapters 11 to 13 though, is the same as in much of the rest of the letter as we have it in our Bibles today: Paul has had it with preachers of success, "super-apostles," who denigrate his ministry. They disdain Paul's apparent weakness, the many adversities he experienced, his poverty, and his alleged lack of spiritual highs.

The Corinthians, as we've discussed in the past few weeks, particularly loved wealth and power. I've mentioned before that one commentator I read recently described Corinth as "the Las Vegas strip of the first-century world." This atmosphere infected the Corinthian church, leaving its members susceptible to the claims of these super-apostles that having lots of money and being well-connected was a sign of God's favor. Paul, they apparently alleged, was not favored by God.

4. But, as alluded to above, the Corinthian Christians valued more than wealth and power. They also put a high value on spiritual highs. They viewed these as signs of God's favor. People who spoke on and on in tongues, or seemed to possess the gift of prophecy, or claimed to have visions and revelations from God, had celebrity status among them, even when the balance of these people's lives displayed nothing of the humility and love of Jesus Christ.

One of the most famous pieces of Paul's writings to the church at Corinth is First Corinthians, chapter 13. It's often read at weddings, which is enirely acceptable, of course. But the situation Paul addresses there wasn't a wedding. He was telling the Corinthians who regarded tongues as the ultimate sign of rightness with God that they were all wet. I speak in tongues, given by the Holy Spirit, Paul asserts. But, he goes on, I would rather you Corinthians speak one intelligible word from God--a word that might bring unbelievers to faith or strengthen the belief of those who are already part of the fellowship--than speak 10,000 words in a strange tongue nobody understands.

"If I speak in the tongues of mortals and of angels, but do not have love," Paul says, "I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal. And if I have prophetic powers, and understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have all faith, so as to remove mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing. If I give away all my possessions, and if I hand over my body so that I may boast, but do not have love, I gain nothing."

Without being grounded in the love of Christ, our spiritual highs are nothing more than faintly curious parlor tricks.

5. Near the beginning of Second Corinthians, chapter 11, Paul says that it's foolishness to engage in a tit-for-tat comparison of ecstatic experiences and visions with his detractors. Paul rarely talks about his experiences of visions, revelations, and such; he wants to talk about Jesus Christ. But, for the sake of elevating Christ and putting the success preachers in their places, he does talk about visions of heaven that he had received.

6. Paul puts these experiences in an entirely different context than the one suggested by the super-apostles, though. They go on about their experiences, using them as proof of their own supposedly heavenly-favored status.

Paul connects these experiences with his weaknesses. Paul asserts that, as commentator Dan Lewis puts it, "true holiness is not a matter of personal power--it is a matter of God's power in the midst of personal weakness."

It's only in the life of those who admit their own weakness that the true power of God can shine through. Self-obsession and a concern with what the world regards as power are both antithetical to a life lived with the God we meet in Jesus Christ.

7. Paul asserts that three different times he had asked God to remove an undefined "thorn in the flesh" from his life. It was sent by Satan, he says. But God had allowed it to continue in order to prevent him from becoming too "elated" with the kinds of mystical experiences of which the super-apostles boasted.

8. That's why I will only boast of my weaknesses, Paul says. God's power is only really seen and experienced by weak people.

This insight is the foundation of the Twelve Step program pioneered by Alcoholics Anonymous. Step One involves an acknowledgement that my addictions are more than I can handle. Step Two is reliance on one's "Higher Power," God, to help withstand the allurements and promises of the addiction in order to become free to truly live.

When we lean on God and refuse to rely on our own power, God's power can do things. When we rely on ourselves, we're like the extra chef in a tiny kitchen; God doesn't have room to do the things in our lives and characters He needs to do.

9. A good Old Testament text to look at in relation to this passage is Judges 6 and 7. It tells the story of how God gave Gideon and the people of Israel a victory in battle. He did so, not by sending more troops, arms, or horses. He did it by whittling Israel's forces down from 30,000 to 300. Without such a whittling, God tells Gideon, the people would be inclined to believe that the victory came from them, their might, or their ingenuity. Only in weakness would they see that victory had come from God. That was exactly what happened.

Commentary on specific verses of this lesson later, I hope.

Monday, July 03, 2006

Speaking of Happiness...

The Poverty That Leaves You Rich

Good Grief

The People Who Make a Difference

The Diet That Will Make You Happy

What Mercy Does

The People Who See God

The People Who Make Peace

Happy When the World Turns Away

And here's a link to a series on happiness written by my blogging friend, Mark D. Roberts:

Happy Time

Good Stuff on the Good Life

I was with a friend the other day and somehow or other we got to talking about how life can feel unfulfilled. The problem stems primarily from society's poor definition of what it means to be happy. In other words, this is a story of two happinesses.Here's a link to Phil's site.

While I was talking to my friend, I managed to recall something that I had once discussed while in philosophy class. It was the difference between psychological happiness and ethical happiness. (Yes, philosophy can actually help you in life.)

Psychological happiness is the happiness we experience when we get a new bauble. We are so happy with a new pair of shoes (we believe they will make us run faster), or a new book (we believe we will learn so much), or a new album (we believe we have finally found the next Beatles); that we cannot contain our joy. There is nothing really wrong with psychological happiness. We are told to enjoy this life, and part of life's enjoyment comes from experiencing new things or getting something that we have worked really hard to possess. I myself am terribly happy with my computer and my room full of books. But, in the end, does it really matter? If all my stuff was taken from me, would I feel bad?

Of course I would. I would be quite put out, and would be justified for being so...to a degree. But, in truth, it isn't things that define who we are as humans, it is happiness. In our society of buy-this-and-be-happy consumerism and deeply jaded sarcasm; we feel happiness constantly being squeezed out of us. Even I can do this from time to time. I will be cruel to someone by taking a joke too far or be so focused on buying something that I don't need, that I need to ask myself, "am I really happier because of this."

Happiness is fragile and strong at the same time. It can be a transient state of mind a la psychological happiness or it can be something deep in our bones. This kind of happiness is called ethical happiness. This is our inherent happiness. It springs from goodness and it is what every human being is searching for whether they know it or not. Don't believe me? Okay, believe Aristotle. He states in the Nicomachean Ethics that, "Happiness then is the best and noblest and pleasantest thing in the world..." Sure, he admits, outside forces definitely contribute to our happiness; but in the end it all comes down to our souls.

Ethical happiness takes all our outside influences and filters them through us. Hopefully when crap happens we can say, "well, that was pretty bad; but at least I am still happy." Its a choice. Aristotle believed that happiness was a gift from the gods. Christians believe that Happiness is God.

God even spoke on Happiness when he was on earth. In the beatitudes the word blessed is translated as happiness as well. This means that we are happily blessed when we are meek or peacemakers or cheese makers (as some British comedians would say, and I am sure that cheese makers are blessedly happy for the most part). We become happy by being virtuous. We become happy by doing what is good, because that is what God does and we live in his universe. Its like moving along with the forces that undergird nature, we can feel that it just makes us happy to be virtuous and to have ethical happiness.

So as we enter into a major national holiday that celebrates a few guys penning a document; I say Jefferson was wrong. We are not pursuing happiness as if it were some outside goal. We are being happy because it is in our intrinsic natures to be happy; and that is the great difference between the two happinesses.

Some Fourth of July Reading

What is the American Dream?

Our Best Presidents?

The Rest of the List

Some Thoughts on George Washington

On Alexander Hamilton

Habits of the Heart:

Part One

Part Two

Part Three

Part Four

Part Five

The Promise and the Perils of Democracy:

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Sunday, July 02, 2006

Happy Independence Day...July 2?

Today, during announcements at the beginning of worship, I mentioned this passage from a letter written by John Adams to wife Abigail on July 3, 1776:

"The Second Day of July 1776 will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America. . . . It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires, and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more."Adams got the modes of celebrating right. We still celebrate Independence Day in these ways. But he got the day wrong.

But he may be forgiven this error. It was on July 2, that the Continental Congress approved severing ties with Great Britain. It was on July 4, that the Declaration of Independence itself was passed by that body.

See more details here.

Is This Bloggish Nepotism? I Don't Care

A few weeks ago, I was telling my son, Philip, that nepotism seems to be a way of life in the blogging world. It's common for bloggers to refer to blogs from their brothers, sisters, fathers, mothers, and seventh-cousins-twice-removed. I think there was a little indignance in my voice as I contemplated big-traffic bloggers bequeathing portions of their readership to relatives while we poor, righteous underlings toiled away in obscurity. (This was the tone I took, I'm sure, although I'm not sure how much I meant it.)

Days later, I casually told Phil that I had linked to a post from his MySpace blog. "Oh," he said, "a little nepotism." Yes, I suppose it is nepotism and Phil is welcome to whoever might click over to his blog on the basis of a mention here.

Here's the part you may find hard to believe: Phil's writing is definitely worth reading. Really...and not just because he's my son. It's because he's thoughtful, insightful,...and funny!

Being a nightowl, he dashes these epistles off while the rest of us are snoring. Waking each day to find them is a bit like experiencing Christmas morning.

But as good a communicator of substance as Phil is, he's an even better person. After worship today, I was talking with a woman who's known him since he was a little boy. "He seems to be able to go to people of any age and care for them," she said. From my biased perspective, that's very true.

Phil is a man of deep loves. He loves God. He loves our country. He loves his friends. He loves to learn. He loves people. He also loves his Mac computer, baseball, alternative rock, and this amazing pageant of human life. It shows in what he writes.

In the upper righthand corner of this post is a picture my wife snapped of Phil during a recent trip to the Sagamore Hill home of Theodore Roosevelt at Oyster Bay, New York. (This is also the place he befriended some Greek Orthodox priests who toured the house with us.)

I'm very proud of both of my kids. This one has a blog and I think it's worth reading. So, it's nepotism. I can live with that.

Here is a link to his site: PowerMadRecluse.

Exploiting Our Opportunities...to Be Generous

Second Corinthians 8:7-15

The subject of generosity was in the news this past week. Investment guru Warren Buffett announced that he was giving 85% of his personal fortune, about $37-billion, to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The press reported that Buffett’s contribution doubled the Gates Foundation’s assets and will evidently provide a big boost in helping that organization pursue its stated goal of wiping out the world’s top-20 killer diseases.

Perhaps inspired by Buffett, action film star Jackie Chan revealed on Friday that in the will he’s currently preparing, half of his fortune will go to charity. Chan’s net worth is presently estimated at $128-million.

I have the feeling that, when hearing these two pieces of news this past week, far from begrudging Buffett or Chan, our sentiments are more like those of the farmer visited by his pastor one day. “If you had two hundred dollars, would you give one hundred dollars to the Lord?” the pastor asked. “Sure would,” the farmer said. “If you had two cows, would you give one cow to the Lord?” “Yeah, I would.” “If you had two pigs, would you give one of them to the Lord?” At this, the farmer's face became beet-red as he told his pastor, “Now, that’s not fair. You know I actually have two pigs.”

We read stories like those of Buffett and Chan or of lottery winners and think, like that farmer, “If I had that kind of money, I would be really generous.”

You’ve probably read what Henry Ford said when asked, “How much money does a person really need?” Ford said, “Just a little bit more.” We might give a similar response to the question, “How much money do you need to have before you become generous?” “Just a little bit more,” we might say, consigning our generosity to the “Someday, I’ll Zone”: “Someday, I’ll be generous with the use of my time, talent, and money,” we say. “But for now, I need to horde as much of it as I can keep.”

In today’s Bible lesson, taken, as the lessons have been for the past several weeks, from the second New Testament letter from the evangelist Paul to the church in the Greek city of Corinth, we’re warned not to cave into “Someday I’ll” thinking. He encouraged the Corinthians Christians--and he encourages us--to be as generous as we can be right with what we have in this moment, through all the moments of our lives.